Break it Down: Chinese Radicals for Beginners

Chinese is a language that has no alphabet, which can be daunting for the Chinese learner. Instead there are characters, over 50,000 of them. However, if you want to learn how to read Chinese, you would only need to know about 2-3,000 characters in order to be able to read a newspaper, but that still leaves you with an awful lot of learning to do. Luckily, the writing system is not without rhyme or reason.

The Chinese language uses radicals or 部首 (bùshǒu), which are the graphical components of the Chinese character. They are essentially building blocks that appear within characters, making them easier to remember.

Alone, most radicals don’t mean anything, but they are combined with other radicals to form the full Chinese characters. There are quite a few radicals that do have meaning by themselves as well.

There are 214 Chinese radicals in all, which is quite a lot to learn! However, rest assured that studying radicals will help you with memorizing the thousands of characters you need in the language. Being able to separate Chinese characters into their components will make it easier to remember them than trying to recall each brushstroke alone.

The best way to start is by learning very common Chinese radicals that appear in lots of characters.

8 Common Chinese Radicals

氵(three drops of water)

This radical is easy to recognize and write. It looks like three drops of water, which isn’t a coincidence! The Chinese name for this radical is literally “three drops of water,” or 三点水(sāndiǎnshuǐ).

You’ll frequently see this on the left side of a Chinese character. While not always the case, this radical often indicates that the character’s meaning is related to water.

Some examples include 河 海 and 游 .

河 means “river,” 海 “ocean” and 游 “swim.” As you can see, these characters all have to do with water.

月(moon)

The moon is an important object in Chinese culture, represented by the Mid-Autumn Festival holiday during which family members traditionally get together to view the moon and eat moon cakes.

The symbol for moon is also a common radical. Be careful though, since in this case, the standalone symbol doesn’t correlate with its meaning. When occurring on the left side of a character, 月 (yuè) has a meaning closer to “flesh,” and is used in a lot of words indicating body parts.

Some characters with the 月 radical include 肚, 脑, 朋, and 服.

肚 and 脑 mean “stomach” and “brain” respectively. 朋 means “friend” or “acquaintance,” and 服 means “clothes.” You can see that a diversity of Chinese characters can be created with the 月 radical.

女 (female)

女 (nǚ) is the Chinese character for female and looks a little like a girl curtsying. Can you guess what kind of words will have a 女 radical?

Some characters that have this radical are 妈, 妹, 姐, 奶 and 嫁.

妈, 妹 and 姐 are female family members: mother, little sister and big sister, respectively. 奶 means “milk,” and 嫁 means “marriage.”

亻 (person)

人 (rén) may be a word you’re familiar with even if you don’t know much Chinese yet. It means “person” or “humanity.”

However, the radical for “person” is 亻, which looks like a compressed form of the character. Character (pun intended) is emphasized in Chinese culture and language, so it is good to become familiar with this radical. 亻 is often used in words having to do with people.

Some characters with this radical are 你, 他 and 伤。

你 means “you,” 他 means “he” or “him,” and 伤 means “wound.”

刂 (knife)

This radical looks like two sharp lines made on a cutting board and, aptly, it is referred to as the “knife” radical.

Usually occurring on the right side of a character, 刂(dāo) is often used in characters that have something to do with cutting, sharpness or the abstract quality of it.

Some example characters are 到, 刻 and 判。

到 means “to arrive,” 刻 “to carve” and 判 “to judge.”

心 (heart)

This heartwarming Chinese radical is a good one to take to heart.

Other than for use in glaringly bad puns, this radical is commonly used in characters having to do with feeling. This makes sense, as the heart, or 心 (xīn), is the place of emotion. This radical is often placed at the bottom of a character.

Some characters that use this radical are 感, 悲 and 忍.

感 means “emotion” in the most general sense. 悲 stands for “sadness,” and 忍 means “to bear or tolerate.”

彳 (travel, going)

This radical is literally referred to as “left step,” after the concept of stepping with the left foot, which is oddly specific!

It may help to know that this radical is mostly used on the left side of a character. It often connotes the meaning of “going” or “travel” in characters. Not to be confused with 亻 (person), this radical has an extra stroke on top.

Some characters include 行, 往 and 徜。

行 means “to walk,” 往 means “toward or bound for,” and 徜 means “to wander.”

宀 (roof)

“At least I have a roof over my head,” the saying goes.

A roof is an important necessity, recognized by the Chinese since ancient times. If you have a roof, you have a place to live. If you have a roof, you have some protection from the elements. As its connotations imply, 宀 (mián) is often used in words related to dwelling or protection. The position of 宀 in a character is often above other radicals.

Some example characters are 家, 守 and 宝。

家 means “home,” 守 “protect or guard” and 宝 “treasure.”

There you have it! Eight useful radicals that you can look for in Chinese texts you come across. Play a guessing game when you come across an unknown character, and see if you can predict the meaning based on the radicals (or at least get close).

Easily read Chinese characters

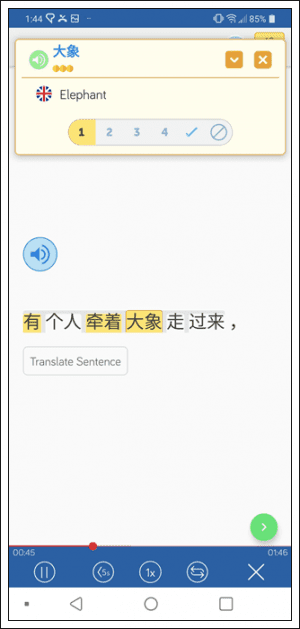

As I mentioned, reading Chinese characters may be a bit daunting but what if I told you there was an easier way. Instead of having to stop what your reading, look up the character’s meaning in a new dictionary, and disrupt your flow, LingQ let’s you easily look up characters with a single tap. Read along transcripts from LingQ’s mini stories or content that you’ve imported easily without having to disrupt your flow!

Looking characters/vocabulary up in LingQ (available for Android and iOS) also lets you hear how they are pronounced using text to speech technology. Of course, when you import movies or music into LingQ, you can read and listen at the same time. Check out LingQ today to discover how to learn Chinese from content you love!

***

Connie Huang has self-studied the Japanese language for over a decade. In addition to Japanese, she knows Mandarin Chinese, Spanish and French.